Put out in September of 1999, this is a good introduction to how the play was written and produced. FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

PRESS OPENING: Saturday, September 18, 1999

Green Highway Theater at Chopin Studio Theater

“We’re supposed to help each other give birth. We’re supposed to help each other abort if it becomes necessary. We’re supposed to help each other die. We’re supposed to help each other live. And we’re supposed to have the knowledge and the strength to do this. And that’s what I learned in the Service.”

• from interview with Judith, Jane: Abortion and the Underground

“We are women whose ultimate goal is the liberation of women in society. One important way we are working toward that goal is by helping any woman who wants an abortion to get one as safely and cheaply as possible under existing conditions.”

• Jane pamphlet, 1969-1973

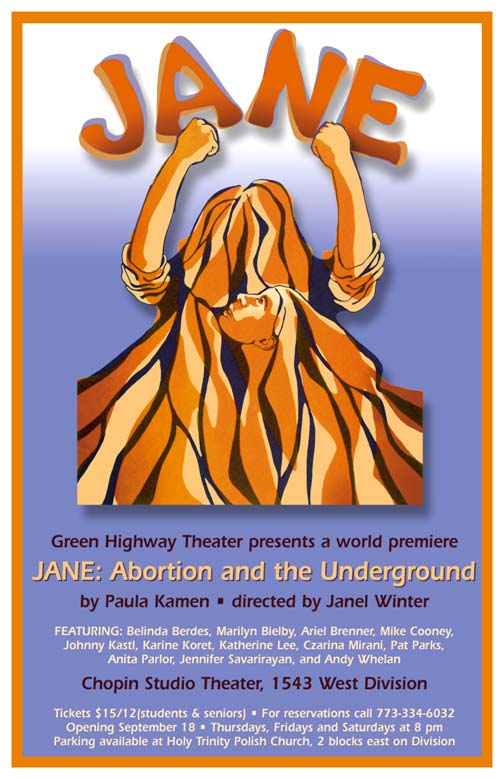

JANE: ABORTION AND THE UNDERGROUND

MAKES OFFICIAL WORLD PREMIERE

CHICAGO – Green Highway Theater announces the long-awaited official premiere of the newly revised feminist drama Jane: Abortion and the Undergroundby Paula Kamen. This two-act play explores “the best kept secret in Chicago,” Jane, an underground abortion service run by Hyde Park women from 1969 to 1973. Unlike most plays that address abortion, Jane: Abortion and the Underground is not an “issue play”; it does not feature debates about abortion’s morality far removed from the reality of women’s lives. Instead, it dramatizes the lives of the women who had abortions and the women who performed abortions through Jane.

Jane: Abortion and the Underground combines scenes detailing the growth of Jane and of Chicago’s women’s movement with the compelling words of the women who actually went through Jane, drawn from interviews and research conducted by Kamen, a nationally respected scholar of women’s sexuality. The story of Jane is the story of the struggle to create access to abortion by a diverse group of women, ranging from a radical student to a happy homemaker to a young black woman who was a dedicated member of both the Chicago Seven defense team and the Girl Scouts. Jane, which was run by a feminist collective of mostly middle-class housewives and students based in Hyde Park, was the one safe alternative for over 11,000 Chicago women of all backgrounds in the years leading up to Roe v. Wade. In all the years of its existence, Jane, which boasted no fatalities and operated in private apartments throughout the city, was well trusted by and commonly received referrals from police, social workers, clergy and hospital staff.

Jane: Abortion and the Underground presents an important piece of both Chicago and women’s history in a way that focuses on telling women’s stories rather than preaching politics.

Jane: Abortion and the Underground opens on Saturday, September 18 at 8 pm at the Chopin Studio Theater, 1543 West Division with an additional show on Sunday, September 19 at 7 pm. Jane: Abortion and the Underground runs Thursdays-Saturdays at 8 pm through October 23. Tickets are $15, $12 students and seniors. Please call 773/334-6032 for reservations, press passes and more information.

PRODUCTION INFORMATION

Jane: Abortion and the Underground is presented by Green Highway Theater, a five-year-old non-profit that focuses on showcasing women’s voices and telling truths about women’s lives. Green Highway has presented the Chicago premieres of shows such as Clair Chafee’s Why We Have a Body and Carolyn Gage’s Louisa May Incest and Calamity Jane Sends a Message to her Daughter. Green Highway Theater’s production of A Book of Ruth was featured in the 1998 New York International Fringe Festival.

Paula Kamen (playwright) is a respected journalist who published Feminist Fatale, a book on young women and feminism in 1991. Her work has appeared in the Chicago Tribune, the Washington Post and Might Magazine, among many others, and was anthologized in Shiny Adidas Tracksuits and the Death of Camp and Other Essays. Her second book Her Way, on young women’s sexual attitudes, will be published in next spring by New York University Press. The research Kamen conducted in the course of writing Jane: Abortion and the Underground was used by the makers of the documentary of Jane: An Abortion Service, quoted in the 1997 book When Abortion Was a Crime, and is on file with the Special Collections Department of the Northwestern University Library.

Janel Winter (director) directed Paula Kamen’s critically acclaimed comedy Seven Dates with Seven Writers for Bathsheba Productions at Chicago Dramatists and ImprovOlympic last fall and winter. She has directed several Green Highway productions, including A Book of Ruth, Softcops and the Chicago premiere of Why We Have a Body. She is a University of Chicago graduate, giving her a special interest in the Hyde Park angle of Jane. She is the president of the Board of Directors of the Women’s Theatre Alliance.

Jane: Abortion and the Underground features Belinda Berdes, Marilyn Bielby, Ariel Brenner, Mike Cooney, Johnny Kastl, Karine Koret, Czarina Mirani, Jennifer Ostrega, Pat Parks, Anita Parlor, Jennifer Savarirayan, and Andy Whelan. Sets are designed by Brian Thompson.

GROUND-BREAKING RESEARCH

Research for the writing of Jane: Abortion and the Underground includes a detailed, original investigation into its past and dozens of interviews with those who were on the scene. This includes clients from various stages of Jane’s development and the major leaders. The drama is stitched from original interview transcripts, fictionalized reenactments of conversations, and historical documents such as newspaper coverage of “The Abortion Seven”, documents produced by Jane, and a script for abortion-rights street theater by the Chicago Women’s Liberation Union. Kamen began her research in 1992 and has been revising the script since 1993.

THE STORY: BEYOND THE SURFACE AND THE RHETORIC

In its compelling drama and occasional dark humor, this play tells an important story in both the history of Chicago and of reproductive rights history. In the ongoing abortion rights discussion, the play presents the much-needed and often overlooked point of view of women, facing the real threat to their lives and human dignity when abortion is illegal. The play also connects the group to its roots in the New Left, civil rights and women’s health movements. Many characters were involved in all these movements, such as Micki, a black civil rights worker who was a legal aide in the Chicago Conspiracy Trial and let Jane use her Kenwood apartment for the procedures. The play also explores connections to the underground Clergy Consultation Service on Abortion, run by E. Spencer Parsons, former dean of Rockefeller Chapel and the University of Chicago, interviewed for the play.

Jane: Abortion and the Underground is also about the power of collective action to make changes in women’s lives. By cooperating under stressful circumstances, Jane made a normally traumatic and “criminal” situation into an empowering one, where in which women often learned for the first time vital information about their own bodies and feminism. Especially in later years, the collective gave personal treatment to clients, giving them health information and, often, copies of the first edition of Our Bodies, Ourselves, as well as emotional support through the process. Jane was also radical in demystifying and taking control of the abortion process, which was considered the domain of the overwhelmingly male medical establishment.

Yet, while addressing politics (which are inextricable from the characters’ lives) the play is more about telling stories than preaching politics. The play explores many complexities of the abortion issue, as well as of the personalities involved. In this play, the complexities of abortion rights are revealed in twists and turns of the plot. Nothing is as it seems on the surface: a minister and pregnant women are abortion rights activists; a policewoman knocking on the door of the Service is seeking and abortion, not an arrest; and the abortion doctor is revealed to be not a doctor at all.

Jane was started by Heather Booth (founder of the Midwest Academy and later a leader in the Democratic National Committee), then a leader of campus activism at the University of Chicago, who is credited with forming more early feminist groups than anyone else. Because of her contacts in the civil rights movement, a friend asked her to find a doctor to help his sister. Soon, the word spread throughout the activist communities of her connection to a doctor, and she found herself setting up a counseling and referral service. When returning calls to women, she used the code name “Jane.” When the demand for abortions overwhelmed her, she sought the help of other activists, many of whom were drawn to the emerging women’s liberation movement. Eventually, Jane officially became a part of the greater women’s movement by affiliating with the Chicago Women’s Liberation Movement, a groundbreaking socialist-feminist umbrella organization founded in 1969.

Gradually, the women of Jane (or “the Service”) began assisting the abortionists and learning the procedures on their own. Meanwhile, they found out the abortionists they were using were not real “doctors” as promised. In 1969, they took over performing the abortions themselves, charging less than $100 apiece and serving the poorest women in the city. After a long period of surveillance, in 1972 the police finally busted the Service. But before the much-publicized “Abortion Seven” could go on trial, the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision released them from charges and Jane dissolved.