Our Band of Sisters

Building Culture and Community in the Chicago Women’s Liberation Union

By Christine Riddiough

Introduction

The Chicago Women’s Liberation Union was formed in 1969 and played a leading role in the women’s liberation movement in Chicago during much of the 1970s. Throughout its history the Chicago Women’s Liberation Union concentrated on organizing women to achieve liberation. CWLU organizing was done with a clear focus on both strategy and theory. In CWLU we spent our time organizing for social change, for a revolution for women. In the process we built bonds of friendship and comradeship that have, in many cases survived for decades. In this article we will explore some of the factors that allowed us to establish and strengthen those bonds and develop a culture of friendship based on action and camaraderie and revolutionary spirit.

In recent retrospectives on the women’s movement of the 1970s feminists have struggled for a word or phrase that captures the bonds we shared as we participated in women’s organizations. Community, camaraderie, fellowship all evoke elements of that relationship, but none really captures it. In talking with friends from that era, we recalled the phrase ‘band of brothers:’

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers; For he to-day that sheds his blood with me Shall be my brother...1

[M]y brave officers; …[M]y noble-minded friends and comrades. Such a gallant set of fellows! Such a band of brothers! My heart swells at the thought of them!2

‘Band of brothers’ has become the catchphrase that evokes the culture of the warrior, a culture that created a bond that cannot be recreated outside of the struggle/the shared battle. But throughout history the intensity of the shared experience of battle could only be shared by men.

In the women’s movement, however, we found our band of sisters, a bond created in struggle and sharing an intensity of commitment not realized in many life experiences. In my case those friendships changed my life through my involvement in the Chicago Women’s Liberation Union (CWLU).

The Chicago Women’s Liberation Union

The CWLU was the first and largest of the socialist feminist women’s unions that were established in the 1960s and 1970s. Activism in the civil rights and anti-Vietnam war movements had left many young women feeling both exhilarated by the prospect of change and disheartened by the failure of the movement(s) to allow them leadership roles or to see them as anything but cooks and secretaries.

By 1967 women’s activism in the Chicago area began to percolate. At the University of Chicago, where Heather Booth was a student, the Women’s Radical Action Project was formed. WRAP was a group of about 40 students and nonstudents at the University of Chicago formed to discuss radicalism and women. An article by Sarah Boyte in the Voice of the Women’s Liberation Movement described one meeting:

Approximately fifty members of the five Chicago radical women's groups met on Saturday, May 18, 1968, to hold a citywide conference. The main purposes of the conference were to create and strengthen ties among groups and individuals, to generate a heightened sense of common history and purpose, and to provoke imaginative programmatic ideas and plans. In other words, the conference was an early step in the process of movement building.3

In April 1968 Heather Booth joined Evie Goldfield and Sue Munaker to write a paper entitle ‘Toward a Radical Movement.’ They described the hopes of many student radicals of day and then noted that while women activists joined with men to try to build a better world, they continued to be left out of the leadership of the movement:

The movement for social change taught women activists about their own oppression. Politically, women were excluded from decision-making. They typed, made leaflets, did the shit-work. The few women who attained leadership positions had to struggle against strong convention.4

The paper went on to describe the status of women in society. They wrote about a new generation of women who

Sense the boredom and bitterness of their mothers. They do not want to be confined to the same roles. They are trying to understand why it is that women are still expected to play subordinate roles.5

They conclude that

… For the true freedom of all women, there must be a restructuring of the institutions which perpetuate the myths and the subservience of their social situation. It is the explicit consciousness of these hopes and analysis which lead us to fight for women’s liberation and the liberation of all people.6

Ultimately this led to a call for the women’s conference. Planning for the conference began in the summer of 1969 and in September a group of more than seven women sent out a proposal for the conference. In that call they described the conferences as

being held for the women who are primarily committed to the development of an independent, multi-issue women’s movement and who see in particular the need to develop program and structures to enable us to get beyond the stage of personal discussions and to reach out to new women.7

They asked people to write working papers on programs and project, strategy and theory. The conference took place in Palatine, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago.

At the conference the political principles of CWLU were adopted along with a structure and initial program. The principles began this way:

The struggle for women's liberation is a revolutionary struggle. Women's liberation is essential to the liberation of all oppressed people. Women's liberation will not be achieved until all people are free.8

The idea of struggle was thus part of the founding of the organization. It was implemented largely through organizing and action which remained the primary focus of the organization until its demise. The first groups within the women’s union were chapters and projects that had started earlier in the 1960s. Many of the chapters were focused on university campuses or in Chicago neighborhoods. Some were projects like Jane, the Abortion Counselling Service that provided abortions to women in the era before abortion became legal. One of the earliest groups to be formed within CWLU was the Women’s Graphics Collective which produced silk-screen posters and other material illustrating the focus of CWLU and women’s liberation more generally. Another of the earliest groups to be formed was the Chicago Women’s Liberation Rock Band which brought a feminist consciousness to rock music.

It is through the chapters and work groups that the bonds of friendship and sisterhood were forged. Through the work of the Graphics Collective and the Rock Band those bonds were strengthened.

The Work Groups

Work groups were the core of the CWLU. They focused on issues or on projects designed to reach out to women in Chicago. They often combined education, service and action components. Over the course of the eight years the CWLU existed, many work groups were formed on issues ranging from health care to economic justice, from lesbian rights to women prisoners. The first work group of CWLU was Jane, the Abortion Counselling Service. Jane was started in the mid-60s in response to the unavailability of abortion. The story of Jane has been discussed extensively in movies and books.9 The CWLU office acted as a channel for women who wanted to get in touch with Jane and when the Abortion 7 were arrested in 1971 CWLU became the focal point for the Abortion Task Force and its work in support of those arrested.

Shortly after the formation of CWLU the Liberation School for Women was established. The brain child of Vivian Rothstein, the Liberation School provided classes in skills, feminism and politics for hundreds of women over the course of the next decade. Rothstein describes the founding of the school:

The Liberation School was born out of the need to offer a place of connection for the many women calling our office wanting to get involved.10

Though today Women’s Studies programs abound, in 1970 they did not exist. The Liberation School provided a way for women from around Chicago to find out about the new women’s movement, to learn skills such as self-defense and auto mechanics and to expand their political horizons. For the members of the work group that ran the school the project was central to their bonds. Out of the school many other projects were born, as women found new strength in themselves and their sisters.

One such group was the Lesbian group, later Blazing Star. In 1971 Liberation School sponsored a class called ‘Women’s Liberation is a Lesbian Plot’ – it was a class where those of us who were gay or were exploring lesbianism could talk and where others who were straight could find out more about the issues facing lesbians. Out of the class a group formed to further the connections between women’s liberation and gay liberation (as it was then known). Over the course of the next few years the group evolved into an activist group that reached out to lesbians to engage them in the movement. The group also worked with other local organizations to educate the wider Chicago community.

Secret Storm is another example of a CWLU project. Its focus was on gaining women access to sports in the Chicago Park District. Title IX of the Civil Rights Act was passed in 1972. It was the basis for many efforts to provide women with equal access to athletics. But in Chicago the ‘old boys club’ still controlled access in the parks. The group believed

…that sports could build women's confidence, create a sense of team effort and help women break out of narrow constricting roles. The Chicago Park District discriminated against women's sports teams, so the battle to get a place to play became a political issue. By 1975, … Secret Storm had 140 women organized into teams. There were angry confrontations with Park District bosses and sexist park users, but slowly women's sports became a fixture in Chicago's parks.11

These are but a few examples of the robust program of the CWLU. They were also the place where we formed our ‘platoons’ in the fight against sexism and patriarchy. Through struggle we formed friendships that became the core of our existence.

The Chapters

In addition to work groups CWLU had chapters which functioned as a combination of consciousness raising groups and political discussion groups. CWLU had its origins in chapters based on college campuses and Chicago neighborhoods. The Hyde Park chapter started as a group in the late 1960s at the University of Chicago. The West Side Group was focused near the University of Illinois Circle Campus and in Evanston a group was established at Northwestern University.

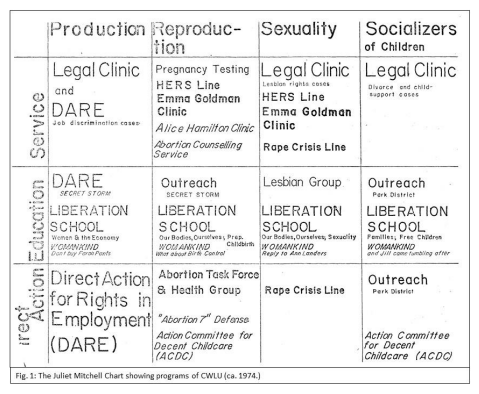

Over the first year of CWLU additional chapters proliferated – on the north side of Chicago, in Edgewater, on the Southwest side. As CWLU evolved the chapters became more like affinity groups – groups that would meet once a week or once every other week to talk about our personal experience and to brainstorm strategy. One of the first of these was the Midwives (originally Midwives of the Revolution). At the CWLU’s second conference in 1971, the Midwives presented a proposal for strategically defining CWLU’s work. The organization adopted the proposal, later called the ‘Juliet Mitchell Chart’ (Fig. 1) because it was based on the work of British Marxist-feminist Juliet Mitchell.12

Two years later the Hyde Park Chapter wrote a position paper, adopted by the CWLU, “Socialist Feminism: A Strategy for the Women’s Movement.’13

Other chapters – Emma Peel, Brazen Hussies, Mrs O’Leary – existed over the course of the eight years of CWLU’s existence. Through them we formed bonds of friendship and gained energy and strength for our struggle. As one CWLU member put it recently, ‘We went to meetings every night of the week in order to advance our fight for women’s liberation.’14

The chapters were also a place where we could share our everyday lives. The frustrations of work, conflicts within families, the joy of a new relationship. There were, of course, conflicts in the groups we were involved in, conflicts often based in personal relationships in those groups. Like the rest of the student movement, we were young and we were experimenting with a new-found freedom. Experiments in ‘free love’ sometimes resulted in the realization that love wasn’t always free. And there were pressures to conform to the women’s movement ‘standard’ of the women-identified woman. Over the course of time, some of these conflicts resolved themselves and some did not. But throughout the existence of CWLU the chapters created bonds that in many cases were never broken.

Women's Graphics Collective

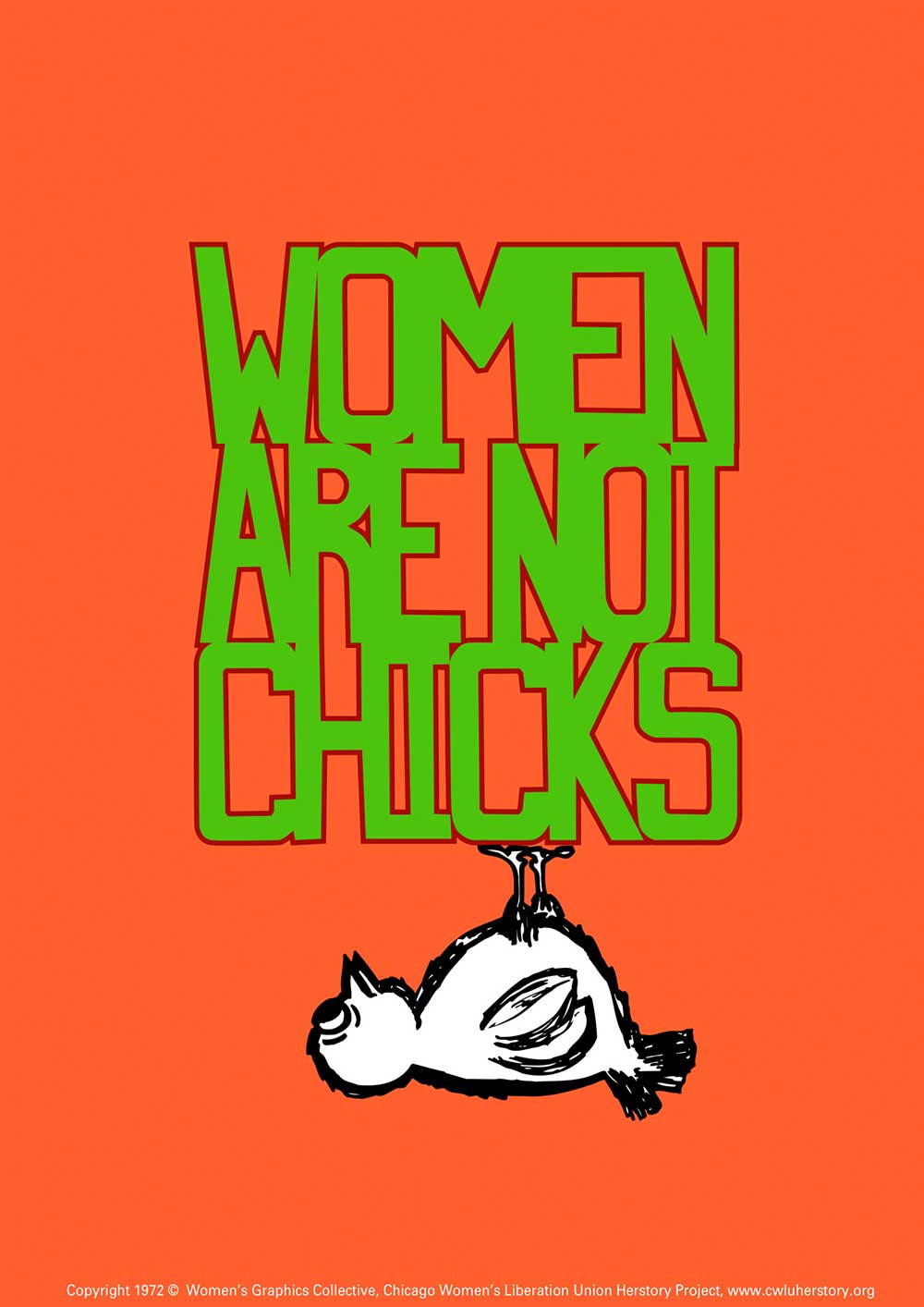

Figure 2. Chicago Women's Graphics Collective Poster

The Chicago Women’s Graphics Collective was formed in 1970 as a work group of the CWLU. The focus of the group was to create art that reflected the values of the new women’s liberation movement:

The founders of the Graphics Collective wanted their new feminist art to be a collective process in order to set it apart from the male-dominated Western art culture.15

The posters range from graphics celebrating International Women’s Day to Lesbian Pride to Women Working. Some are almost lighthearted in the joy they proclaim for the new women’s liberation movement; they include slogans like ‘SISTERHOOD IS BLOOMING – SPRINGTIME WILL NEVER BE THE SAME’ (Fig. 2) and ‘WOMEN ARE NOT CHICKS’ (Fig. 3.) Some of the posters advertise projects of the CWLU like the Liberation School for Women and the Chicago Maternity Center project. Still others reflect the international perspective of CWLU like the International Women’s Solidarity poster with the phrase ‘Women – Many Waves One Ocean’ and the Mountain Moving Day poster with the poem by Japanese writer Yosano Akiko and the picture of an African woman freedom fighter (Fig 4.) Still others showed the many issues that CWLU addressed from child care to abortion to rape to economic justice.

The Graphics Collective was indeed collective in the way it operated. ‘Poster thinks’ each week involved collective members discussing ideas for posters and working together to design them. An article from the Chicago Tribune describes the rationale for the joint poster-making process:

Art, after all, was always supposed to be the expression of some mystical kernel of self, some artistic erogenous zone stimulated in private for the tangible sublimation of the socially sanctioned ego.

These women, however, had enough of that before they found each other. Stilled by the thought of working alone in quest of the “Great Masterpiece,” they decided to combine their talents with their concern for women’s politics, price the objects within nearly everyone’s reach, and address themselves to a new audience that “doesn’t have to know an artist’s name to recognize a ‘good painting.”16

Figure 3. Chicago Women's Collective Poster

The posters created a link between the political activities of CWLU and the quest for a richer culture. In this they reflect the consciousness of the CWLU position paper, ‘Socialist Feminism: A Strategy for the Women’s Movement.’ Authored by the Hyde Park Chapter of CWLU, the paper reflects in its introduction the broad nature of women’s liberation and the connection between, politics, community and art:

One is the direction [of the women’s movement is] toward new lifestyles within a women's culture, emphasizing personal liberation and growth, and the relationship of women to women. Given our real need to break loose from the old patterns--socially, psychologically, and economically-- and given the necessity for new patterns in the post revolutionary society, we understand, support and enjoy this tendency.

Figure 4. Chicago Women's Collective Poster

The other direction is one which emphasizes a structural analysis of our society and its economic base. It focuses on the ways in which productive relations oppress us. This analysis is also correct, but its strategy, taken alone, can easily become, or appear to be, insensitive to the total lives of women.

As socialist feminists, we share both the personal and the structural analysis. We see a combination of the two as essential if we are to become a lasting mass movement.17

The posters adorned the CWLU office providing nourishment for the mind and soul. Through their vivid imagining of our spirit of feminism they reinforced the bonds of sisterhood.

CWL Rock Band

The music of ‘the movement’ tended to be folk music – from Pete Seeger to Peter, Paul and Mary. The women’s movement had its own folk/pop singers. Everyone in the women’s movement in the `970s remembers concerts by Holly Near and Meg Christian, Kristen Lems and Margie Adams. But in Chicago and for most teenagers in the United States, what really got everyone going was rock music.

But, as Naomi Weisstein says, rock music was so misogynist18. So in 1970 as the CWLU got started, Weisstein decide to reach out to young women in Chicago by forming the Chicago Women’s Liberation Rock Band. Her vision for the Rock Band:

It would have us singing about how smart, strong, and hip we were, and how we would have sex only on our own terms, thank you. And we would get so good that soon we would saturate the airwaves, inundating teenage girls with a new kind of musical culture – joyful, playful, funny, and taking no shit from no one. Sort of like the much later Pussy Riot.19

They played gigs at events like International Women’s Day and at coffeehouses and universities. Audiences were joyful – the new music had energy and spirit. They played many dances and toured from New England to Colorado. But Chicago was their home, as Weisstein says:

We thrived as a chapter under the CWLU tent. While we toured, we also played all over Chicago whenever we were needed by CWLU, at conferences, dances, and Chicago street demonstrations. We stayed and played.20

They wrote their own music with a feminist rock sensibility. Some were new lyrics to older songs, like ‘Papa Don’t Lay That Shit on Me:’

Papa don’t lay that shit on me, you just don’t turn me on Papa don’t lay that shit on me, the fun and games are gone It wasn’t my game / it wasn’t my fun All that trashing is over and done Papa don’t lay that shit on me, you just don’t turn me on.21

Other favorites included ‘Ain’t Gonna Marry:’

I ain‘t gonna marry / I ain‘t gonna settle down Ain’t gonna marry /Ain’t gonna settle down I’m gonna stay right here/And celebrate a freedom that I found.22

And ‘Mountain Moving Day’ based on a Japanese poem (and also featured on a Graphics Collective Poster):

The mountain moving day is coming I say so yet others doubt it23

The Rock Band was a chapter of the CWLU and also an integral part of our band of sisters. It was a political group whose mission was guided by the political principles of CWLU, an outreach group dedicated to bringing the ideas of socialist feminism to audiences throughout the Chicago area, and it was also the rock on which our community was built. It brought us together as sisters, whatever political differences we might have. It crossed the borders of politics and culture, as Hilary Reser describes:

Indeed, its effective melding of political intent and purpose with cultural creation demonstrates the inadequacy of singular and distinct definitions of both "culture" and "politics." … the avowedly political CWLRB embarked on a cultural course of action in the larger fight against patriarchal oppression. It used the cultural realm as a weapon, as a tool of engagement in the battle to create a more egalitarian society.24 Through its music, comedy, joy and laughter the Rock Band cemented the bond we shared in the CWLU.

Conclusion

There was a camaraderie, a community, in the Women's Union that was nowhere else to be found. Our sense that we were united for a purpose, that we were working toward a goal of women's liberation meant that all our interactions, be they social, political or cultural contributed to that effort. There were always debates and differences of opinion but those were combined with a commitment to long-term struggle.

Movies, books, web sites have discussed the community created by the women's movement and other movements, but do they really capture the spirit and community of the Chicago Women's Liberation Union? For it was more than community that we had, we were more than neighbors talking over the backyard fence. We discussed what things would be like 'after the revolution' knowing that revolution was what we were about. When we wrote letters we signed them 'yours in struggle' or 'yours in sisterhood.'

And that was what we were - sisters in struggle. We felt we were in a war against the patriarchy, against capitalism. That made it worthwhile to undertake the many bold actions and programs that we established, but no action was too small if it made a difference. Going to meetings five nights a week wasn't a sacrifice - it was what we did. The meetings, the discussions, the fights and the demonstrations all gave meaning to our lives in ways that most of us have not experienced since.

This was reflected as well in the capacity to reconnect with one another, sometimes after decades of absence. In emails, in get-togethers, and, more often lately, in memorial services, we greet one another and pick up the discussion where it left off. We recognize that that experience from the 1970s has shaped each of our lives in many ways.

We were, of course, so very young then - 18, 20, 25 and with that youth was both a certain naiveté and a sense of expectation of what the world held for us. It allowed us to do things that would previously have been unthinkable:

- we counselled people who needed abortions and some of us performed those abortions; we did not hesitate to help when help was needed;

- we joined the speakers' bureau and went to high schools to talk about this new idea of feminism;

- we circulated petitions for gay and lesbian rights in working class Chicago neighborhoods;

- we worked with janitresses to fight Mayor Daley and city hall for fair wages.

And in our hope and work and expectation for change, we built friendships that have sustained us for decades. And they have given us a sense of joy in the work still to be done. In a talk at the Boston University Conference ‘A Revolutionary Moment: Women’s Liberation Movement in the late 1960s and early 1970s‘, Heather Booth, one of the founders of CWLU summed it up this way:

A saying on one of the posters of the Chicago Women’s Liberation Graphics Collective that Estelle Carol convened, was “Sisterhood is Blooming: Spring time will never be the same.” And that is just how I feel. About the women’s liberation movement and about this wonderful conference and being here with my sisters.25

- 1Shakespeare, William, Henry V, Act IV Scene iii, The St. Crispin's Day speech.

- Southey, Robert, Life of Nelson, (G. Bohn 1861), page 127 - quoting Lord Nelson.

- Sarah Boyte, “From Chicago,” Voice of the Women's Liberation Movement, June 1968.

- Heather Booth, Evie Goldfield and Sue Munaker, Toward a Radical Movement, Unpublished April 1968.

- Booth, Goldfield and Munaker, Toward a Radical Movement.

- Booth, Goldfield and Munaker, Toward a Radical Movement.

- Barbara Alter, Carol Ackerman, Liz George, Vivian Rothstein, Alice Keller, Hedda and others, Proposal for a Chicago Radical Women’s Conference to be Held October 31, November 1 & 2, Unpublished, September 2, 1969.

- The Political Principles of the Chicago Women’s Liberation Union, adopted November, 1969.

- Laura Kaplan, The Story of Jane: The Legendary Underground Feminist Abortion Service, The University of Chicago Press, 1995.

- Vivian Rothstein, “The Liberation School For Women, A Project Of The Chicago Women’s Liberation Union,” (paper presented at ‘A Revolutionary Moment: Women’s Liberation Movement in the late 1960s and early 1970s‘, Boston University, March 28, 2014.)

- CWLU Herstory Committee, Outreach/ Secret Storm http://www.uic.edu/orgs/cwluherstory/CWLUAbout/storm.html.

- 12 Juliet Mitchell, “The Longest Revolution,” New Left Review, no. 40, December 1966.

- Hyde Park Chapter of CWLU, “Socialist Feminism: A Strategy for the Women’s Movement,” Unpublished, 1973.

- Penny Pixler, Private conversation, March 2013.

- Description from the cwluherstory website at http://www.uic.edu/orgs/cwluherstory/CWLUGallery/graphcoll.html.

- Linda Winer, “Posters That Express the Reality of Being a Woman,” Chicago Tribune, February 11, 1973.

- Hyde Park Chapter of CWLU, “Socialist Feminism: A Strategy for the Women’s Movement.”

- Naomi Weisstein, “Reaching out to Teenagers with Revolutionary Feminist Music: The Chicago Women’s Liberation Rock Band 1970-1973,” (paper presented at ‘A Revolutionary Moment: Women’s Liberation Movement in the late 1960s and early 1970s‘, Boston University, March 28, 2014.)

- Naomi Weisstein, “Reaching out to Teenagers with Revolutionary Feminist Music: The Chicago Women’s Liberation Rock Band 1970-1973.”

- Naomi Weisstein, “Reaching out to Teenagers with Revolutionary Feminist Music: The Chicago Women’s Liberation Rock Band 1970-1973.”

- Words by Naomi Weisstein and Virginia Blaisdell, “Papa Don’t Lay That Shit on Me,” from the album Papa Don’t Lay Shit on Me.

- Words by Susan Abod and Jennifer Abod, “Ain’t Gonna Marry,” from the album Papa Don’t Lay Shit on Me.

- 23 Music by Naomi Weisstein, words by Yosano Akiko and Naomi Weisstein, “Mountain Moving Day,” from the album Papa Don’t Lay Shit on Me.

- Hillary Reser, " ‘One By One You're Gonna Know Our Power’ The Chicago Women's Liberation Rock Band and the Politics of Cultural Transformation,” (seminar paper presented at the University of Chicago under the direction of Professor Amy Dru Stanley, 2004. It is available at http://www.uic.edu/orgs/cwluherstory/CWLUGallery/seminarpaper.html#_ftnref28.

- Heather Booth, “Chicago Women’s Liberation Union: If we organize we can change the world. But only if we organize!” (paper presented at ‘A Revolutionary Moment: Women’s Liberation Movement in the late 1960s and early 1970s‘, Boston University, March 28, 2014.)