By Christine R. Riddiough and Margaret Schmid

Abstract

The Chicago Women’s Liberation Union was formed in 1969 and played a leading role in the women’s liberation movement in Chicago during much of the 1970s. Throughout its history the Chicago Women’s Liberation Union concentrated on organizing women to achieve liberation. Not limited to legal equality, the CWLU envisioned a society free of sexism in education, the family, the media, employment, health care, and all areas of social life. CWLU organizing was done with a clear focus on both strategy and theory. Understanding strategy and theory is often difficult – immersion in developing a theory often prevents one from actually being an activist. But without a theory and a strategy that flows from it, our activism can be mindless and even counterproductive.

In CWLU we understood that neither strategy nor activism would get us very far unless we had a theory that linked them. In the theory we developed we acknowledged that the struggle for women's rights was not isolated from other struggles – we recognized the intersection between gender, race and class and the importance of ensuring that our theory, strategy and actions bridged those intersections. We also recognized that our activism had to relate to the conditions facing women in a concrete manner in order to communicate the liberating potential of the women’s movement.

This paper explores critical documents that show the effort in CWLU to provide a theory and strategy as the basis for the organization’s action programs. It contextualizes the work of CWLU and suggests lessons for today’s feminist activists.

Introduction

The Chicago Women’s Liberation Union was formed in 1969 and played a leading role in the women’s liberation movement in Chicago during much of the 1970s. Throughout its history the Chicago Women’s Liberation Union concentrated on organizing women to achieve liberation. This organizing was done with a clear focus on both strategy and theory. In this paper we will examine several documents that demonstrate CWLU commitment to organizing and the connection between that organizing and the theory and strategy underlying it.

In this paper, we review:

- documents from the founding conference and from the organizers that show that the main focus of the work of the organization was achieving real gains for women;

- the political principles of CWLU adopted at the 1969 founding conference. They provided the basis for the organization’s theory and action;

- the ‘Juliet Mitchell Chart’ named after the British Marxist-feminist and author of ‘The Longest Revolution’ and proposed by a chapter of CWLU as a strategic tool;

- the position paper ‘Socialist Feminism: Our Strategy for the Women’s Movement’ outlining three strategic goals for projects that CWLU undertook to:

- win reforms that objectively improve women's lives;

- give women a sense of their own power, both potentially and in reality; and

- alter existing relations of power.

- the paper on ‘Leading CWLU into Outreach’ that discusses the importance of outreach in building the women’s movement.

The Documents

The Founding Conference: Documents from the founding conference and from the organizers show that the main focus of the work of the organization was on achieving real gains for women. The first of these documents, “Toward a Radical Movement”1 , was written in the spring of 1968. The document highlights the focus of the movements of the 1960s and notes that those movements ‘for social change taught women activists about their own oppression.’

The paper went on to describe the history of women in the workplace from the 1940s until the late 1960s. The increased involvement of women in the workplace in the World War II years resulted in a taste of economic independence for women and an understanding of the importance of collective action for them as workers. The paper noted that the authors knew of no models for an egalitarian marriage nor was the supposed sexual liberation of the 1960s a real benefit to women.

The paper concluded by stating:

For the true freedom of all women, there must be a restructuring of the institutions which perpetuate the myths and the subservience of their social situation. It is the explicit consciousness of these hopes and analysis which lead us to fight for women’s liberation and the liberation of all people.

As a whole, the paper presages three important aspects of CWLU theory and strategy. First, that the movement for women’s liberation is inextricably linked to other movements for social justice. Second, that to achieve real liberation for women requires that women as a group organize. Finally, for women to achieve liberation, changes in institutions as well as individual consciousness are key.

‘A Proposal for a Chicago Radical Women’s Conference’3 was circulated in the fall of 1969. It called for a conference ‘for women who are primarily committed to the development of an independent, multi issue women’s movement and who see in particular the need to develop program and structures to enable us to get beyond the stage of personal discussions and to reach out to new women.’ Suggestions for working papers for the conference asked participants to ‘state the broader theoretical assumptions and implications of your suggestions for the development of the women’s movement.’ It also sought papers on strategy to deal with questions like the relationship of the women’s movement to the larger social justice movements of the time.

As both of these papers indicate, the founders of CWLU were concerned with both a theoretical perspective that would encompass women’s liberation as part of and essential to a broader movement and with developing a strategy that would incorporate women from around the city of Chicago into a movement to achieve liberation for women.

The Political Principles: The documents described above foreshadowed the statement of political principles that was adopted at the October 1969 founding conference of CWLU. They provided the basis for the organization’s theory and action and stated:

The struggle for women's liberation is a revolutionary struggle.

Women's liberation is essential to the liberation of all oppressed people.

Women's liberation will not be achieved until all people are free.

We will struggle for the liberation of women and against male supremacy in all sections of society. We will struggle against racism, imperialism, and capitalism, and dedicate ourselves to developing a consciousness of their effect on women.

We are dedicated to a democratic organization and understand that a way to ensure democracy is through full exchange of information and ideas, full political debate, and through unity of theory and practice.

We are committed to building a movement that embodies within it the humane values of the society for which we are fighting. To win this struggle, we must resist exploitative, manipulative, and intolerant attitudes in ourselves. We need to be supportive of each other, to have enthusiasm for change in ourselves and in society, and to have faith that people have unending energy and ability to change.

Several things stand out in reading these principles. The first three lines neatly summarize the position of the founders and reflect their backgrounds as part of the student, anti-Vietnam War and civil rights movements. Yet, unlike many position papers and statements of the era, they are succinct. They clearly position women’s liberation as a part of a larger revolutionary movement and as essential to that movement.

The women who founded CWLU and many of the early members were involved in political activism through the movements of the 1960s. Heather Booth, one of the authors of ‘Toward a Radical Movement’ had participated in the 1964 Freedom Summer and in student actions at the University of Chicago. Vivian Rothstein, an author of the call for the conference5 had traveled to Vietnam and met with women from their National Liberation Front. For them, as for other women of their generation, these activities gave them the energy to fight on behalf of women and a keen awareness that the progressive movement was still primarily led by men and that even the most active women were marginalized when decisions of any consequence were made. Out of this arose a consciousness that, if women were to be liberated, women had to be made central to the struggle.

The fifth sentence links the struggle for women’s liberation explicitly to the struggles against racism, imperialism and capitalism. The experiences of women in the movements opposing these forces made it clear that the fight for women’s liberation was not separate from the efforts of other oppressed people in the United States or around the world.

The last segments illustrate how the theories embodied in the other elements of the principles related to the development of an organization and to the importance of organizing. Again, unlike many left organizations of the period, CWLU emphasized putting the principles into practice, both in terms of the organizational structure and in terms of the importance of reaching out to women not yet in the movement.

Over the life of CWLU, only one change was made in the political principles – this was a modification to the fourth sentence in the principles: “We will struggle for the liberation of women and against male supremacy in all sections of society.” In 1972 this statement was revised as follows:

We will struggle for the liberation of women and against sexism in all sections of society. Included in this struggle is the struggle for the right of sexual self-Determination for all people and for the liberation of all homosexuals, especially lesbians.

The impetus for this change came from lesbians in CWLU who felt it was important to incorporate support for lesbian and gay liberation in the principles in the principles. When the principles were first adopted in 1969, the new gay liberation movement had barely begun. No gay pride parades had been held, no lesbian feminist festivals established, Stonewall was still a whisper in the background, but by 1970 CWLU had started to incorporate lesbian and gay liberation into its program. In the summer of 1970 the connection between gay and lesbian issues and women’s liberation was discussed at a meeting sponsored jointly by CWLU and the women’s caucus of the Chicago Gay Alliance. This led to further discussion within CWLU and ultimately the adoption of the principle above and a position paper on ‘Lesbianism and Socialist Feminism’.

It is also interesting to note the change from male supremacy to sexism. In 1969, the word sexism was not in general use, but by 1972 the word sexism was used to denote the institutional nature of the oppression of women. The change in the political principles reflected this understanding.

In addition to the political principles, CWLU also adopted a structure to guide its work. Like most local women’s organizations of the time, CWLU was democratic in nature, but unlike many groups CWLU did have a structure. It consisted of a steering committee to guide the organization and included representatives of chapters and work groups within CWLU. Further, from the beginning, CWLU had staff, recognizing that the enormity of the struggle for women’s liberation required a way to focus and move forward that volunteers alone could not provide. Over the course of its existence, over 90 chapters and work groups were formed. Ultimately the chapters combined political discussion with consciousness raising and personal support, while work groups focused on projects aimed at advancing women’s liberation. Much of the theory and strategy for CWLU was developed in the chapters.

The Juliet Mitchell Chart: Over the course of its existence, CWLU adopted several papers proposed by chapters that helped direct the work of the organization. The first of these was the ‘Juliet Mitchell Chart’ named after the British Marxist-feminist. Presented by the Midwives Chapter of CWLU at its second conference (1971), the chart provided a way to link the work of the organization with both the theory and strategy. The paper they wrote (in their words):

will argue for a program and strategy which emphasizes struggle on many different levels, none of which is a clear priority over the others, and none of which is adequate without the development of the others.

They proposed the chart as a way to visually understand and plan the work of the organization. In its original version, one dimension of the chart listed the areas of women’s oppression: production, reproduction, sexuality and socialization of children. These areas of oppression were based on Mitchell’s pamphlet, The Longest Revolution8 (reprinted in Woman’s Estate9 ). Mitchell traced the evolution of socialist views on women from Charles Fourier, August Bebel and Karl Marx to Simone De Beauvoir and Kate Millet. She noted that, “De Beauvoir’s main theoretical innovation was to fuse the ‘economic’ and ‘reproductive’ explanations of women’s subordination by a psychological interpretation of both.” Mitchell described Millet’s contribution in Sexual Politics as establishing, “that within patriarchy the omnipresent system of male domination and female subjugation is achieved through socializing, perpetuated through ideological means, and maintained by institutional methods.”

Mitchell went on to describe the contributions of radical feminists like Shulamith Firestone to the understanding of women’s oppression and exhorted the new movement to simultaneously recognize the “necessity of radical feminist consciousness and of the development of a socialist analysis of the oppression of women.” She then described her view of the oppression of women:

The key structures of woman’s situation can be listed as follows: Production, Reproduction, Sexuality and the Socialisation of Children. The concrete combination of these produce the ‘complex unity’ of her position; but each separate structure may have reached a different ‘moment’ at any given historical time. Each then must be examined separately in order to see what the present unity is, and how it might be changed.10

The pamphlet described these areas of oppression, noting that while women are often denied the opportunity to enter the workforce,they are nonetheless also subject to oppression in the context of the family through their role in reproduction, sexuality and socialization of children. She concluded that:

for an authentic liberation of women … to occur, there must be a transformation of all the structures into which they are integrated, and all the contradictions must coalesce, to explode – a unite de rupture. A revolutionary movement must base its analysis on the uneven development of each structure, and attack the weakest link in the combination. This may then become the point of departure for a general transformation. What is the situation of the different structures today? What is the concrete situation of the women in each of the positions in which they are inserted?11

This pamphlet was very influential in CWLU and was the basis for extensive discussion and planning. But the Midwives chapter did not stop with Mitchell; they recognized that the understanding of women’s oppression must be combined with a strategy to fight that oppression. In their chart, they incorporated that strategic approach. The original chart had four areas of work: struggles around immediate needs of women, consciousness raising/educational work, development of analysis and strategy, and developing a vision and building alternatives. They showed how the chart might be used, using as examples some of the early activities CWLU had organized and supported:

They also recognized that:

this is just a two dimensional chart. It helps us look at different types of program necessary to organize around women's oppression as women. But it is clear that women are not only oppressed as women, but are also part of all other oppressed groups within this society (e.g. blacks, workers, students, gay people). Because of women's interrelatedness to all of society we must have a view of program which says that our oppression as women cannot be separated from the oppression of all other groups. That means that our movement must work on program which struggles against all kinds of oppression and must respond specifically to the ways the oppression of these groups affects women in them12.

A discussion of the proposal was held at the second CWLU conference in April 1971. A lively debate resulted in the adoption of the chart as a tool for CWLU planning and strategy. In the course of the debate, the strategic areas were changed to reflect the outward oriented work of the organization. Struggles around immediate needs of women became direct action; consciousness raising/educational work was called education; building alternatives became service. Development of analysis and strategy and developing a vision were viewed as part of the internal work of the organization which largely fell to chapters. Throughout the remainder of CWLU’s existence, the Mitchell chart guided the organization’s work. An example is given in table 2.

The Mitchell chart was also used to advance the theoretical perspective behind CWLU strategy. An example is the work of the Lesbian group of CWLU. In 1972 it proposed that CWLU adopt the position paper Lesbianism and Socialist Feminism13 . The paper started by noting that:

to understand how women's oppression and gay people's oppression are related to each other, and to discover the relationship of lesbianism to the women's movement, we need a deeper understanding of the structure and functioning of our society. In this paper we want to examine these questions from our perspective as socialist-feminists.

It went on to describe, using the areas of oppression from the Mitchell chart, the intersection between women’s oppression and that of lesbians and gay men. The paper suggested that a more complete understanding of the oppression of gay men and lesbians involved going beyond the obvious issue of sexuality to issues related to production, reproduction and socialization of children. At the end of the paper, a strategy for organizing on LGBT issues was discussed using the Mitchell chart to provide context:

The Chicago Women's Liberation Union operates with a three part strategy of service, education and direct action. At the present time, educational and service programs are perhaps the easiest to relate to gay oppression, and direct action struggles more difficult.

Table 2: An example of how the Mitchell Chart was used.

CWLU developed programs in each of the areas of the chart as table 2 illustrates. The primary education programs were the Liberation School for Women, WOMANKIND newspaper and the Speakers’ Bureau. Each of these programs focused on the whole range of issues defined in the Mitchell chart. Service programs of CWLU included the iconic Abortion Counselling Service (‘Jane’), the Legal Clinic and the Rape Crisis Line. Action programs ranged from Action Committee for Decent Childcare (ACDC) to workplace organizing with the Chicago City Hall janitresses (Direct Action for Rights in Employment) to demanding equity for women in Chicago Park District sports programs.

Socialist Feminism: A Strategy for the Women’s Movement: Two years later, in 1973, CWLU adopted a position paper, ‘Socialist Feminism: Our Strategy for the Women’s Movement’14 . Written by the Hyde Park Chapter, this paper outlined in more detail the ways in which women are oppressed and provided three strategic goals for projects that CWLU undertook:

- projects must win reforms that will objectively improve women's lives;

- projects must give women a sense of their own power, both potentially and in reality; and

- projects must alter existing relations of power.

The introduction to the paper described the competing perspectives within the women’s movement of the time:

One is the direction toward new lifestyles within a women's culture, emphasizing personal liberation and growth, and the relationship of women to women. Given our real need to break loose from the old patterns--socially, psychologically, and economically--and given the necessity for new patterns in the post revolutionary society, we understand, support and enjoy this tendency. However, when it is the sole emphasis, we see it leading more toward a kind of formless insulation rather than to a condition in which we can fight for and win power over our own lives.

The other direction is one which emphasizes a structural analysis of our society and its economic base. It focuses on the ways in which productive relations oppress us. This analysis is also correct, but its strategy, taken alone, can easily become, or appear to be, insensitive to the total lives of women.

As socialist feminists, we share both the personal and the structural analysis. We see a combination of the two as essential if we are to become a lasting mass movement. We think that it is important to define ourselves as socialist feminists, and to start conscious organizing around this strategy.

The paper’s five sections laid out a comprehensive approach to organizing:

- Socialist Feminism - the concept and what it draws from each parent tradition.

- Power - the basis for power in this society, and our potential as women to gain power.

- Consciousness - the importance of consciousness for the development of the women's movement, its limitations, and its place in a socialist feminist ideology.

- Current issues and questions facing the movement - a socialist feminist approach to respond to and develop a context for our programs and concerns.

- Organization - the importance of building organizations for the women's liberation movement and some thoughts on organizational forms.

Section I detailed the idea of socialist feminism and described its roots in the traditions of socialism and feminism. It incorporated a feminist perspective that recognized that the institutions of sexism and capitalism combine to oppress women. It then provided a detailed analysis of society and gave examples of the kind of changes it viewed as desirable but not obtainable in current society. It concluded that:

- We must reach most women. We must work toward building a majority movement. Our analysis tells us this is possible if we proceed in the right way.

- We must present intermediate goals that are realizable as well as desirable to show the necessity and possibility of organizing

- We must develop collective actions.

Perhaps the idea of power and the role it plays in women’s oppression and the necessity of women gaining power to gain liberation was the most important idea detailed in the paper:

As socialist feminists we have an analysis of who has power and who does not, the basis for that power and our potential as women to gain power. Sisterhood is powerful in our personal lives, in our relationships with other women, in providing personal energy and maintaining warmth and love. But sisterhood is revolutionary because it can provide a basis on which we can unite to seize power

The remainder of the paper discussed specific issues. It concluded by reiterating the three point strategy: ‘1) win reforms which really improve women's lives, 2) give women a sense of their own power through organization, 3) alter the relations of power.’ It said:

Primarily, we argue for an aggressive and audacious perspective. It is one that our movement began with when we thought we were the newest and hottest thing going. Now, we have found roots. We will need strategy, organization and so many steps along the way. But we must take the offensive again, and this time fight a long battle--worth it because we believe we can win.

Throughout its history, CWLU included a focus on direct action. The Socialist Feminist paper put this into perspective. The Hyde Park chapter, which drafted the paper, also gave birth to the Action Committee for Decent Childcare, a program aimed at revising licensing laws for child care centers in Chicago and getting the city to provide funding for centers. Working women, who had limited access to childcare, joined the effort. They staged an action in the office of the city official responsible, at first seeking a study on child care in the city. When the official did not respond, the group took further action, ultimately leading to some of the licensing reform and funding demands they had made initially.

Later in the 1970s CWLU’s Secret Storm work group worked with women in the Chicago Park District to ensure that women had equal access to Park District sports facilities such as playing fields and equipment. These are but a few examples of how CWLU put theory into action.

Leading the CWLU into Outreach: Another perspective that guided the work of CWLU is described in a paper on ‘Leading CWLU into Outreach’16 . Written by Jenny Rohrer and Judy Sayad and influenced by their work on Park District equity for women, it discusses the importance of outreach to women beyond those in CWLU:

Outreach means getting to know a lot of people; it means bring women's consciousness and politics into the everyday lives of people.

It is the whole process of meeting women, talking to them about their lives, about women's liberation, and offering them programs - to use and to work on. It is how we initially mobilize and educate masses of women to begin to take control of their lives, to see their personal problems as political, and to use the tools of service, education, and direct action to make their lives better.

The idea behind outreach was to get women outside the core group of CWLU involved in the organization and in the movement as a whole. It recognized that simply involving the same 100 or 1,000 women in activities would not result in the liberation of women. Overall, CWLU programs addressed many of the issues women faced, but did not always connect with women:

Our programs speak to many of the specific needs in women’s lives, and we have to take our programs out; we have to talk to women who have never heard of a women’s liberation union about their lives and women’s liberation.

Outreach was not an additional tactic to be added to the Mitchell chart nor was it opposed to direct action, rather it was a way to approach all CWLU work.

This paper provided examples of what outreach would look like in the context of a range of CWLU programs. By offering services in many neighborhoods in Chicago, the Pregnancy Testing program could provide a nucleus for neighborhood women’s organizations. Each CWLU program - from the Health Evaluation and Referral Service to the Legal Clinic - could make better use of WOMANKIND newspaper as a way to get the word to women around the city.

The outreach group also worked to encourage high school and junior college students to get involved in women’s liberation. Through the distribution of leaflets in girl’s bathrooms, young women who might not have heard of women’s liberation got involved in CWLU activities. Work in the Park District began when women’s softball teams were displaced by men’s teams. Women from CWLU worked with the softball teams to challenge the division of resources. Secret Storm spread the word among the players and described other activities for women.

The lesbian group published its own newsletter, Blazing Star, which was distributed to lesbian bars in Chicago. This group worked with bar-sponsored softball teams to encourage more women in the lesbian community to join the women’s movement.

These and comparable efforts in other CWLU work groups aimed to involve women from Chicago’s working class neighborhoods and thus expand its constituency of women.

Discussion

To fully understand the implications of these documents, we need to reflect on the context in which they were created. CWLU was the first and largest of the women's liberation organizations established in the United States during the 'second wave' of the women's movement in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Like women's liberation activists around the United States, CWLU members were, on average, in their 20s when they were involved in CWLU. While data on these women is limited, there are some resources that can be used. Feminists Who Changed America17 includes brief biographies of many women who were active in the women's movement in the 1970s. Approximately 32 women associated with CWLU are listed. The median and mean for year of birth is 1943. The data is slightly skewed because two of the women listed were born before 1930. Over 80% were born in the period 1941-1951 Generally, they had some college or were college graduates; few were married or had children.

For most of these women their formative years were the 1950s and 1960s. Many became politically active in high school and college and their activism was informed by the student movement, the civil rights movement and the anti-Vietnam war movement. This has been documented for women in the women's liberation movement generally by Sara Evans18 and is reflected in unpublished interviews19 of members of CWLU by Margaret Strobel, Professor Emerita of Gender and Women’s Studies at the University of Illinois Chicago. While books like The Feminine Mystique20 and The Second Sex21 had an impact on these women, that impact generally occurred after they had already been influenced by their experiences as activists in other movements.

As a result there was a predisposition to understand the movement for women's liberation as part of the larger movement for peace and justice. The documents described above clearly reflect this link. Furthermore, involvement in these other movements also predisposed CWLU members to view the oppression of women as part of a larger system of oppression, rather than simply the result of the actions of individual men. The theories described in the paper Socialist Feminism: A Strategy for the Women's Movement22 clearly demonstrate this.

In some respects, this is not different from what happened in many other groups at the time. The 1960s and 1970s saw the proliferation of many left-oriented political groups, but what was unique about CWLU (and other groups like the Twin Cities Women's Union that were modeled on CWLU) was the explicit connection between theory and organizing. From its beginning CWLU focused on organizing women. The use of the Juliet Mitchell chart promoted the theories articulated by Mitchell herself and the focus on using these theories to actually guide activism. Socialist Feminism: A Strategy for the Women's Movement23 highlights the importance of understanding and changing the relations of power. Leading the CWLU into Outreach24 focuses on the need to involve women from many different communities in the struggle for women's rights. It recognized that women’s liberation would not be achieved until women from social groups beyond those initially involved in the 1970s feminist movement were involved and unless their concerns were clearly addressed.

The connection between theory, strategy, organizing and activism is, many respects, unique.

Despite internal controversies, CWLU and many of its projects lasted for eight years before it disbanded in 1977, much longer than any of its sister counterpart organizations. How and why CWLU disbanded is the subject of another paper (Riddiough, 2014) and won’t be addressed here. Its longevity was due to the fact that its members were able to make these connections and its activities were sustained by them. Even after disbanding, projects of CWLU like Blazing Star (the lesbian group) and HERS (Health Evaluation and Referral Service) were sustained for several years. Many individual members continued their activism as staff and leaders of other organizations, including NOW and several unions, their lives having been changed and enriched through their participation in CWLU.

From the experience of CWLU and from the documents described above, we conclude that theory and strategy are at the service of organizing and activism and effective organizing is dependent on the development of theory and strategy.

What are the lessons learned? First, we can and should learn from the work that has gone before in order to build a better, stronger women’s movement today. One of the weaknesses of the women’s movement of the 1960s and 1970s was the lack of knowledge of previous efforts in the struggle for women’s rights. One theme heard over and over in interviews with activists from that period was ‘we knew nothing’ - that applied to sex, reproduction, finances and history. History books might have a sentence or two on the women’s suffrage movement. That lack of knowledge led us to reinvent the idea of feminism. Today young feminists need not do that if they learn the lessons of the past.

A second lesson is that to be effective, organizing must be done strategically, and that victories are not necessarily lasting. At present, the political right and its War on Women demonstrate the importance of having a long-range strategic view; this is perhaps seen most clearly in the rollbacks of reproductive rights over the last several decades. Internet petition drives, hashtags that disappear in days will not, by themselves, be an effective counter to that right-wing war. Feminists - young and old - must reconsider how to more effectively use the theoretical and strategic tools to inform and enhance our organizing.

While CWLU spent time and energy on discussing theory - and some would say the amount of time and energy was far too great - the primary focus of those discussions was on what could advance the work of the organization rather than on reifying theory. CWLU projects were developed with a consciousness of theory and an understanding that the fight for women's liberation could not be merely an unrelated set of skirmishes, but rather a coordinated battle against systemic oppression.

Conclusion

As described in its position papers and many other documents, CWLU was an explicitly revolutionary organization. It was founded based on the idea that simple reforms like equal pay for equal work would not be enough to achieve women’s liberation, but with the knowledge that such reforms were an important step toward liberation.

The theory behind the efforts of CWLU was grounded in the idea that socialism and feminism both contributed important perspectives to understanding women’s oppression, and that together were essential to providing a real framework for action.

Organizing – education, service and direct action – formed the core focus of CWLU. Outreach to women around the city was viewed as central to building the organization and the movement. Integrating the action and outreach approaches often proved to be a formidable challenge, but through projects ranging from the Liberation School for Women to WOMANKIND, to work on child care, reproductive rights and services, rights of city workers, rights of lesbians and gays, and opportunities for women in athletic programs, CWLU worked to achieve women’s liberation and left a history to be proud of and learn from.

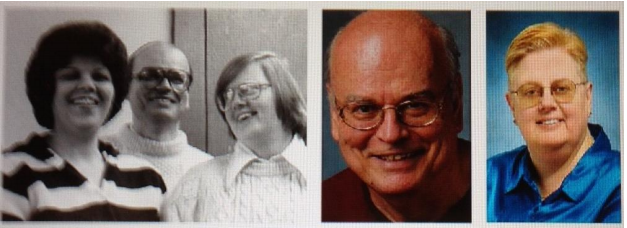

Biography

Christine R. Riddiough was active in CWLU in the 1970s, a major author of Lesbianism and Socialist Feminism and leader in Blazing Star. She later worked for NOW and the Gay and Lesbian Democrats of America. She currently teaches computer programming and statistics and lives in Washington DC.

Margaret Schmid was a member of the Midwives Chapter, the Womankind Work Group, the Speakers Bureau, and co-chair of CWLU steering committee. After working as a college professor and subsequently a public sector labor union leader, she is retired and lives in Chicago.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the staff of the Chicago History Museum and the Northwestern University Library for their assistance in retrieving archival material. The original documents are available in digital form from the authors by emailing criddiough[at]igc.org.